All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

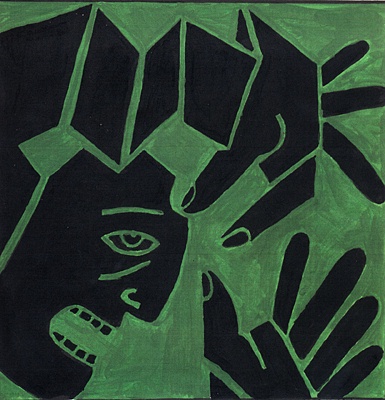

Los Borrachos (The Drinkers) MAG

I used to tell Don Artemio that I would become a cop just to arrest him for drinking. He would laugh at me for being so silly. On one occasion I threw away Uncle Beto's beer, and he got mad. I was staggered by his reaction. He was as mad as he would get if he caught my sister and me making a mess. His brow wrinkled and his mustache no longer made him look humorous and soft; instead, it made it him look like the scary person he was not. I had been so proud for doing it, but after that I learned never to touch a man's beer.

Beer was always a part of my family life. The first time I had some was when I was very little. The women spent their time upstairs, but the men in my family and their friends lived another life in the basement. They would sit in their plastic chairs talking and drinking. I would curiously walk into their hangout and observe their social life. One of them thought it would be funny if I had some beer. Don Artemio handed me a cold bottle cap filled with Corona. I took a sip of the men's magical drink, expecting the most wonderful taste in the world. I thought I would be initiated into the men's secret society. Instead, I received disappointment. I drank the beer in disgust, puckering my face and forcing the liquid down my throat. They laughed at my innocence. From that day on, I vowed to never drink beer.

As I got older I found another reason to abstain from drinking. It turned the men into children. They would cry, speak in inaudible slurs, and tell me their pitiful life stories. Alcohol gave them the amazing ability to trip on perfectly flat surfaces. Every party or family gathering, there were cases of Heineken, Corona, and Miller Lite. The men would gather in their corners and be best friends, appreciating each other for spending $15 on a case of beer. By the end of the night they sometimes were enemies, or they just continued to sound ridiculous. They did not seem like men to me. Dozens upon dozens of glass bottles would litter the house.

The women would watch their husbands in disapproval, but never say anything. It was difficult to get the childish men home. The women had to help their husbands walk, ignoring their senseless comments and stuffing them into the back seats.

Sometimes the drunks were funny, but as time passed I became more and more bothered by it. It was hilarious to watch them sing mariachi songs on the karaoke, but I hated when their other sides emerged. I hated when Uncle Beto would tell me about his regrets about his daughters back in Mexico, or when Uncle Saíd would complain about not being able to see his daughter. It was always his ex-wife's fault. It never occurred to him that he was not trying hard enough. I was just a kid. What was I supposed to tell them? They wouldn't want to hear what I really thought.

Jesús, my Tía Ede's husband, had sobered up – a nice change for the family. It was hard for Jesús, though. He didn't say so, but I saw it. Whenever someone refused a drink, Don Artemio would insist, “Come on, just one! It won't hurt! Be a man!” The drunks would tear a man's pride apart if he rejected a drink, almost as if they resented his self-control. It was harder for him to be accepted by them. It was even harder when most of the family consisted of women, with only that small group of men. I always respected the man who did not give in.

Don Artemio told the same stories over and over when he was drunk. He would introduce me to everyone and say, “This one is really smart!” waving his index finger at the person he was talking to, then staring off blindly in the wrong direction. “I'm so proud … she used to be so small! Up to here.” He would smile, showing his missing front teeth, and hold his hand near his waist. “She used to scream at me a lot. Ha ha. One time she got mad because I took the beers out of the car first instead of her backpack. She said her bag was more important. Oh, this one … she called me Nana-Termio.” He would pull me close and I would smile in embarrassment. The uninterested stranger would grin shyly and look at me in pity. These episodes usually ended with him crying and telling me that he loved me like his own granddaughter.

The worst was when Don Artemio complained to us about how unappreciated he was. “I do so much for this family! No one says thank you! Why don't I get any respect around here?” These rants usually happened after he'd descended to his jewelry workshop in the basement. He would come up hours later with bloodshot eyes. He would walk through the hallway, supporting himself against the white walls decorated in family photos. Sometimes he was quiet after spending hours singing his ranchera music and playing guitar. I knew the lyrics to “Llorar y Llorar” because of him. His stereo loudly played the violins, trumpet, and guitars. Vicente Fernandez sang about crying and crying.

You will tell me that you didn't love me, but you will be very sad, and that's how you will stay. With money and without money, I will always do what I want. I am the king.

When Don Artemio was quiet, he was oblivious, and my sister and I would whisper to each other and laugh at him.

At some point the women got tired of the drunks. They would call them cucarachas aplastadas – like squished spiders, they would say. The women would gather and talk about how absurd the men were, drinking and wearing their gold rosaries. When the men spoke their muffled nonsense, the women would respond with “¡Ya ya, callate!”

Don Mario was the worst. He would even get drunk on days when there were no special occasions. I could not understand how his liver supported him. He was my great-grandmother's husband. When he got drunk he had the sudden ability to speak English, though most of his vocabulary was swear words he would blurt out in a drunken Spanish accent. I detested when he spoke to my great-grandmother disrespectfully. “Your great-granddaughter is too loud. She does not behave.” Who was he to criticize my behavior? I could not stand to watch her remain quiet. Her small frail body and arched back would walk to the kitchen to bring him his dinner. She should have done what my grandmother Paula did. She stopped cooking for him. My great-grandmother could have at least made Don Mario serve himself.

I watched these women my whole life. I watched them remain quiet, and I did too. I wanted them to say something because I did not have the power to. The men had the power. They would not listen to me or the women. All I could do was sit at family parties wondering why the men were the way they were, and accept that that was life. I could not do anything then, but as I grew older I knew I could prevent myself from being in that place. By choosing to not drink as an adult, I have the control.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 2 comments.